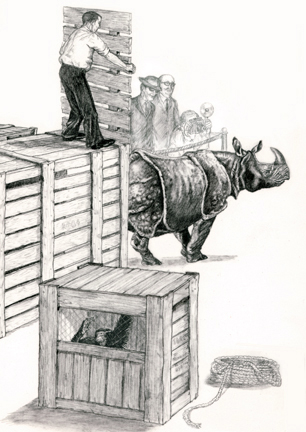

When the time came for the ocean voyage, the two Indian rhinos walked docilely into their shipping cages. Like many captive rhinos, they were quite tame and not easily upset. Unk’s behavior was predictable. He gave the handlers more trouble than the two huge rhinos together. Nevertheless, the young siamang was finally placed in his cage and loaded onto the ship. For the second time in his life, Unk was about to visit the United States, this time to become a permanent resident.

The ship sailed from England on a clear, bright summer day. The weather soon changed. For days on end, the ship pitched and rolled ceaselessly in the heavy seas of a North Atlantic summer storm. It was not the sort of weather designed to bring out the best in Unk’s personality. But instead of jumping around, screaming and biting, as everyone had expected, Unk acted frightened and withdrawn. He did not feel well. Like the two rhinos traveling with him, the siamang was seasick.

Bad weather persisted nearly all the way across the Atlantic. Unfortunately for Unk, the journey by water was not over when the ship reached America. It sailed the St. Lawrence Seaway to the Great Lakes all the way to Milwaukee.

In the summer of 1959, most of the new Milwaukee Zoo was still under construction. The Primate House, however, was open for business, with a variety of monkeys and apes in modern enclosures. The new primate cages were spacious and well-equipped, with shelves, ladders, exercise wheels, bars, ropes, hanging chains, and tires, giving the intelligent, active primates many opportunities to play.

Unk was examined by a veterinarian, who pronounced him healthy, if a little difficult to handle. The young siamang was fully recovered from his seasickness, and he quickly settled down in his new enclosure in the Primate House. But most of the people who came to the zoo spent little time watching Unk. They preferred exhibits of monkey families, where there were often babies to watch. Or else they liked Samson, a gorilla who had been in Milwaukee since he was a baby. Now, at age ten, he was a huge, impressive animal. Everyone wanted to watch Samson, the king of the Milwaukee Zoo. Zoo visitors, like the reporters who had greeted Unk, just did not seem interested in a solitary siamang.